Serving the Guest: A Sufi Cookbook

Essays | Recipes | Gallery

One of the traditional roles of the dervish lodge was as community kitchen and hostel, providing food and shelter for the poor and for travelers. Many early Sufis were "sons of the road," wandering during the warm season, and relying on the grace of God and the spontaneous generosity of fellow Sufis for shelter and sustenance. Followers of other faiths also could count on such generosity, with no questions asked about their religion.

A kitchen in which meals were cooking around the clock was the hallmark of many Sufi saints. The great Chishti Shaikh Nizamuddin Auliya was known to entertain large groups of traveling dervishes — even thirty or more — for up to three days at a time. The three-day limit is in keeping with Muhammad's counsel: "Hospitality extends for three days, and anything beyond that is charity." Ibn Batuta enjoyed and documented such hospitality during his travels in the 14th century, as did Evliya Efendi in the 17th century.

The desire to share food was one basis for the development of communities — the Turkish word tekke referred to a refectory or dining hall long before it became exclusively identified with a Sufi establishment. With the development of orders and communities came a greater capacity to serve greater numbers; but no matter what its size, each Sufi center had lodgings reserved for guests, and a place of honor for them at the table.

The Persian word langar was synonymous with a soup kitchen and resting place for travelers, or a Sufi residence. Ahmed Uzgani's largely mythical "History of the Uwaysis," set in East Turkestan around 1600 CE, includes stories of Sufi saints who established langars and spent years in this way of service. Legend has it that the kitchen of one of them, Ghiyath al-Din of Shikarmat, was miraculously granted a limitless supply of fire and water. The many references to holy men and women engaged in such work reflect the great value attached to it, and the widespread presence of langars throughout Central Asia.

Abdul Qadir Gilani, pir of the Qadiri Order, was known as Ghauth al-'Azam, "The Great Helper," and was renowned for his charity. According to the Qadiris, he was 'born of love, lived in a perfect way, and died having achieved the perfection of love." One of his characteristics was generosity, and the tradition which he started of feeding the poor is perpetuated every year by his followers on his urs, the anniversary of his death. On the 11th day of Rabi'al-Thani, at his shrine in Baghdad and throughout the Muslim world, thousands of people gather at meetings and festivals to recite Qur'an, to honor the memory of Abdul Qadir Gilani, and to partake of the large quantities of food cooked and distributed in his honor.

Following the example of their founder, Muinuddin Chishti, Chishti khanqahs have always kept open kitchens and have provided vital services in public emergencies. In 1976, when monsoon floods destroyed many houses in Ajmer, India, the Chishti khanqah there fed and housed many of the homeless. For centuries the Ajmer Langar Khana has cooked and distributed twice daily a barley porridge, itself known as langar. In 1904 the Rajputana District Gazetteer reported:

From the 15th to the 19th centuries CE, the Ansari caretakers of the shrine of Ali in Balkh (now Mazar-i-Sharif, Afghanistan) offered to all comers a meal of bread and soup every Friday and Monday evening; and when they could afford it, sweets and fruit were set out after Friday and Monday evening prayers. The 16th Century Helveti Shaikh Ibrahim ibn Muhammad Gulshani established a dergah in Cairo which became widely known for its public offerings of food; its staff included a baker, a cook, and a "tablesetter for the poor."

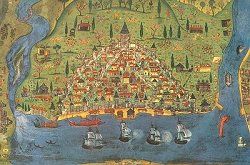

In Ottoman lands, the imaret was a public institution serving travelers, the needy, dervishes, and the keepers of the mosques. The public kitchens of the imarets and many of the Sufi tekkes and zawiyas (all of which had open kitchens) were supported by waqf, charitable foundations established by government, and by wealthy and prominent men and women. Support also came from private donations and from the dervish orders' agricultural activities and industries. (For instance, for centuries the Bektashi Order controlled the most productive salt mines in the Ottoman Empire; the salt from those mines was called Hajji Bektash salt.) In the 16th century, the Istanbul imaret of Sultan Mehmed II Fatih prepared meals for over 1,100 people every day; its guest house accommodated up to 160 visitors at a time. Stores of cheese, cream and honey were earmarked for guests, and those fortunate enough to attend a banquet there were served special rice dishes such as dane and zerde.

Sufis have carried this tradition of service into modern times. Although Kemal Ataturk outlawed the Turkish dervish orders in 1925, in the 1930's Mevlevi Shaikh Suleyman Loras was permitted to open the kitchen of a Mevlevi tekke in order to feed the poor. Three evenings a week the Karagum Helveti-Jerrahi dergah, located in a poor section of Istanbul, accommodates 500 or more diners. Many local community residents come for dinner and leave after the meal, to be replaced by others who come to participate in dhikr. The Jerrahi dergah in Spring Valley, New York, serves 125 or more diners every Saturday night, and even more — and more frequently — during the month of Ramadan. Once a month, community members directly distribute cooked meals, person to person, to local families in need.

In Rufai dergahs throughout Turkey, tables are routinely set for 200-250 people. During Muharram, the Tirana, Albania, Bektashi tekke prepares ashura, a pudding of legumes and dried fruits, for 600 people. Throughout the year at the Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship in Philadelphia, 50 to 200 people take their evening meal together every night.

In modern Egypt, offerings of food and hospitality are central to Sufi life. The Sufi center or saha offers meals and lodging to guests; some have enormous concrete tables accommodating one hundred of more diners at a sitting. At annual moulid observances honoring the anniversary of the death of Sufi saints, khidamat — hospitality stations — are set up in tents, at nearby buildings, or on simple cloths laid out upon the ground. Guests are offered food and drink, called nafha — a word with the dual meaning of "gift" and "fragrance." Nafha must be accepted, for not only is it a gift of the heart, but it carries with it the baraka of the saint being honored. Poor people partake of nafha for its nourishment; poor and rich alike partake of nafha for its baraka.

Dervish hospitality in the grand manner was described by an American guest of the Shaikh of the Tripoli Mevlevi tekke in the 1920's:

We found ourselves[...] sipping a delicious pale-green liquid, mixed from freshly crushed white grapes and lime juice... The luncheon was an Arabian Nights feast of more than twenty courses and lasted for two hours. Whole roasted chickens, and chicken pilaf with rice, almonds, and raisins; lamb on skewers; lamb wrapped in grape leaves and cooked in olive oil, lamb stewed with eggplant; lamb cooked with peppercorns; delicious salads; cucumbers peeled at the table and eaten as we eat fruit; no less than six desserts, beginning with a great pan of custard, running the gamut of pastries with ground-up nuts and honey, to end at last with watermelons cooled in the fountain.

[...] through all the exuberance of his welcome, through the elaborate material luxury of our entertainment and his obvious whole-hearted enjoyment of the delicious food, I sensed continually that there was another side to this man and felt that his abundant physical vitality was not incompatible, perhaps, with powers which might be equally unusual in other directions. I had been told that he was a great mystic, and I was not prepared to doubt it on the superficial evidence.

Six hundred years earlier, that Shaikh's Pir had written:

that's why they eat so much!

But the Sufi who takes nourishment from the light of God

is free from the shame of begging.

Such Sufis are one in a thousand,

the rest live under their protection.

Both guest and host stand at the threshold between the known and the unknown worlds, between the mundane and the sacred. Whether the material setting be opulent or simple, the ultimate value of the relationship lies in the degree to which both are willing to reflect the divine qualities. The offering and acceptance of an invitation reflect the willingness of guest and host to render service and honor, to identify with each other, and to acknowledge that, in fact, there is no other. Knocking at the door, opening it in welcome, sharing company at the hearth, breaking bread in fellowship — these actions mirror the inner capacity for unconditional acceptance of the hospitality and sustenance God offers to all creatures. The epitome of such openness was depicted by the Hungarian traveler Arminius Vambery, who in 1862 was a guest in the tent of Allah Nazr, on the plateau to the north of Gomushtepe, Anatolia:

Whether he wore the robes of a Bektashi or not, it is clear that Allah Nazr understood the words of Hajji Bektash:

from Serving the Guest: A Sufi Cookbook

Copyright © 1999, 2000 by Kathleen Seidel

Sources of previously published material by other authors used by permission, and print sources for images, may be found at http://www.superluminal.com/cookbook.