Serving the Guest: A Sufi Cookbook

Essays | Recipes | Gallery

I was raw, I roasted and I burnt.

The Mevlevi kitchen with its large hearths was both the place where the meals for the tekke were prepared, and its school for spiritual development and socialization. There potential dervishes were cooked, ripened, and prepared for service as devoted members of the order. The kitchen was also the place where dervishes learned to turn, feet revolving around a nail embedded in a raised section of the floor.

To become a dervish, an applicant was required to undergo a chille, a 1001-day trial by service. This commenced only with the permission of his family or guardian if he was young. The Shaikh would explain to him the difficulties of the path and try to discourage him from entering the tekke. If he remained determined, the novice was guided to the saka postu, a pelt set to the left of the kitchen entrance. He would sit there for three days to think, reflect, and observe the activities of the tekke. Kneeling silently on his pelt, head bowed and inclined to one side, he ate what was given him, and prayed and slept in the same spot.

Three days later he would be reminded that he could reconsider and leave immediately. If he chose to stay, he was taken to the Kazanci Dede — the Keeper of the Cauldron and Master of Service — who sent him back to the kitchen to spend the next 1001 days in service. His training as a dervish was completed in this manner.

The first eighteen days were full of errands: fetching, carrying, performing menial tasks. The novice was given sharp commands, and was required to accept each one with equanimity and willingness. If he was unsuccessful, one night while he slept his shoes would be turned outwards at the door. He was then expected to leave the tekke at first light, without protest, and never return.

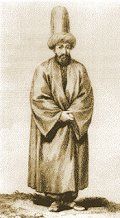

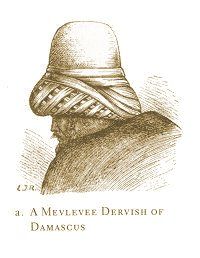

On the other hand, if he fulfilled the requirements and the other dervishes felt that he was qualified, they would notify the Kazanci Dede, who would then send him to the Asci Dede, chief of the kitchen and master of novices. The Asci Dede would invest the novice with a cap, bless it and place it on his head; and give him a tennure, the dervish dress. The novice then set his own clothes aside.

The dervish-elect would return to the kitchen to complete his service under the supervision of the Kazanci Dede. He was required to do whatever was asked of him without complaint, and work with others in the service of the tekke. He underwent numerous trials and tests during his chille. For example, if he were told to buy tobacco from a certain shop, he had to go to that exact shop, even if others were nearer. This tested his patience, fortitude and behavior. His faults were pointed out to him, and if he persisted in them, his shoes would be pointed toward the tekke door.

Kitchen chores included washing dishes, fetching water, scrubbing and sweeping, shopping, setting the table, and lighting candles. Novices served the senior dervishes in person, with tasks arranged in order of importance. The worst job, cleaning latrines, was given in the final days of service as yet another test of patience and self-effacement.

The 1,001-day chille involved eighteen levels of trials and tests. If the novice successfully approached the end of this period, he would be sent to the Meydanci Dede, the Chief Steward and Master of Ceremonies, who was responsible for the administration of the tekke. The Meydanci Dede would then call throughout the tekke to all of the other dervishes: "Destuur! He has complete his service. His chille will end in a week. Let it be known and all prepared!"

On the day of the initiation ceremony, the novice was taken to the baths, where he was presented with the full garb of a dervish. He was then seated on the saka postu, where he sat on his very first day at the tekke. Towards evening an eighteen-branched candelabra was lit in the kitchen, sherbet was prepared, and tables were set for a celebratory meal. Amid the chanting of prayers, the novice then took the vows of initiation, and the sikke, the traditional dervish headdress, would be placed on his head. He then was guided to his room and the door closed behind him.

from Serving the Guest: A Sufi Cookbook

Copyright © 1999, 2000 by Kathleen Seidel

Sources of previously published material by other authors used by permission, and print sources for images, may be found at http://www.superluminal.com/cookbook.